Australia is fast approaching a silent sovereignty crisis – one not defined by foreign troop movements or tariffs, but by terawatts and server racks.

The world is entering an era where national advantage will be measured not only in military strength or trade surpluses, but in compute capacity – the raw processing power needed to fuel artificial intelligence. And without a dramatic fall in energy prices, Australia will be left outsourcing this capability to countries with cheaper, more reliable power.

This is no longer theoretical. Compute is the beating heart of AI, and compute requires energy. A lot of it. In fact, leading tech firms now talk about AI buildouts in terms of megawatt-hours (MWh), not chips or servers. Training a large language model like GPT-4 reportedly consumes over 1.3 gigawatt-hours – enough to power 1,000 Australian homes for a year.

The nations that can host this infrastructure at scale will reap the economic and strategic benefits: data sovereignty, medical breakthroughs, productivity gains, defence automation, financial modelling, and scientific leadership. The rest will rent access – effectively leasing decision-making power from overseas.

This isn’t a future risk. It’s already happening.

Take Amazon’s recent decision to invest US$20 billion (A$31 billion) in two massive data centre complexes in Pennsylvania. The clincher? One will be powered by an adjacent nuclear power station. When was the last time a comparable investment landed on Australian shores? Tech giants are looking for two things above all: cheap, stable energy, and policy certainty. Right now, Australia offers neither.

The brutal economics of AI infrastructure

Australia’s wholesale electricity prices remain among the highest in the developed world. Despite boasting abundant solar, wind, gas, and uranium reserves, our fragmented energy policies, regulatory delays, and ageing grid make large-scale compute unattractive.

To illustrate: in the US, industrial energy prices average around 9–10 cents per kilowatt-hour. In Australia, even before recent volatility, prices hovered around 15–20 cents/kWh in key markets. When scaled across tens of thousands of GPUs running 24/7, that difference becomes a billion-dollar penalty.

AI models don’t just need to be trained; they need to run continuously, fine-tuning search, finance, logistics, agriculture, and more. Without local AI compute centres, that processing is exported offshore. In time, that means the logic underlying key personal, medical, and economic decisions will increasingly reside in foreign jurisdictions.

It’s not hard to see the sovereignty concerns: who owns the data? Where is it stored? Under what legal regime is it processed? And whose interests does it ultimately serve?

The real danger is this: one day, your child could be diagnosed by an AI model trained overseas, in a system built by people who don’t share our values — and if that system decides their life isn’t worth saving, there will be no recourse, no explanation, and no appeal.

If not us, who?

Singapore, the UAE, Canada, and the Nordics are all aggressively courting AI infrastructure. Norway is offering green hydropower and ice-cold climate advantages; the UAE offers tax concessions and speed. Meanwhile, Australia continues to dither on nuclear energy, bicker over transmission infrastructure, and delay long-promised energy market reforms.

Even the Albanese government’s flagship Future Made in Australia policy has yet to meaningfully address the energy cost question for compute. Encouraging AI R&D and ethics frameworks is important, but meaningless if there is nowhere affordable to run the models being developed.

But don’t we have data centres?

A potential rebuttal to concerns about Australia’s role in AI infrastructure is that “we already have data centres.” It’s true that Australia hosts a number of world-class data facilities, particularly clustered around Sydney and Melbourne. But let’s be clear: data centre are not AI compute centres.

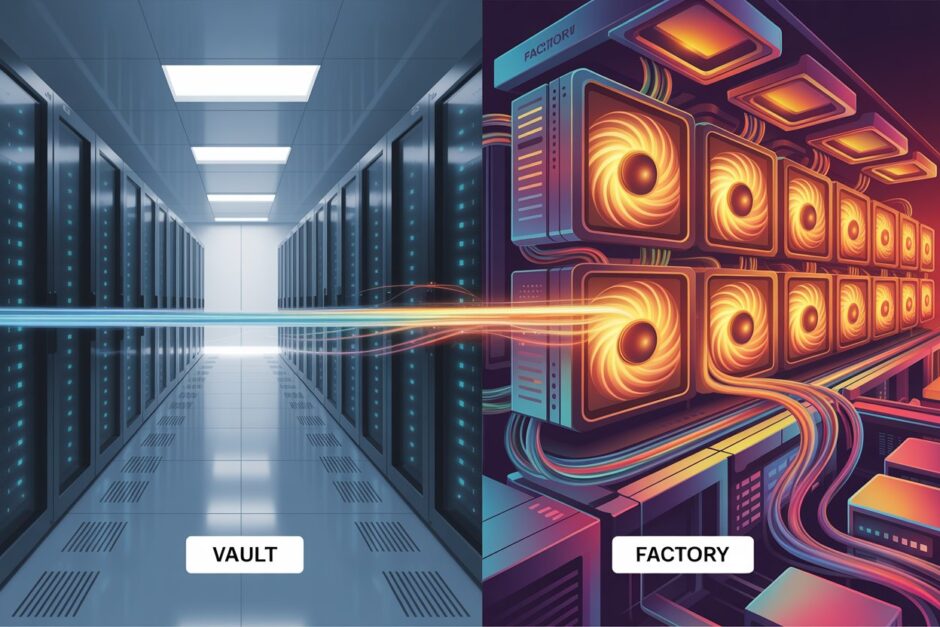

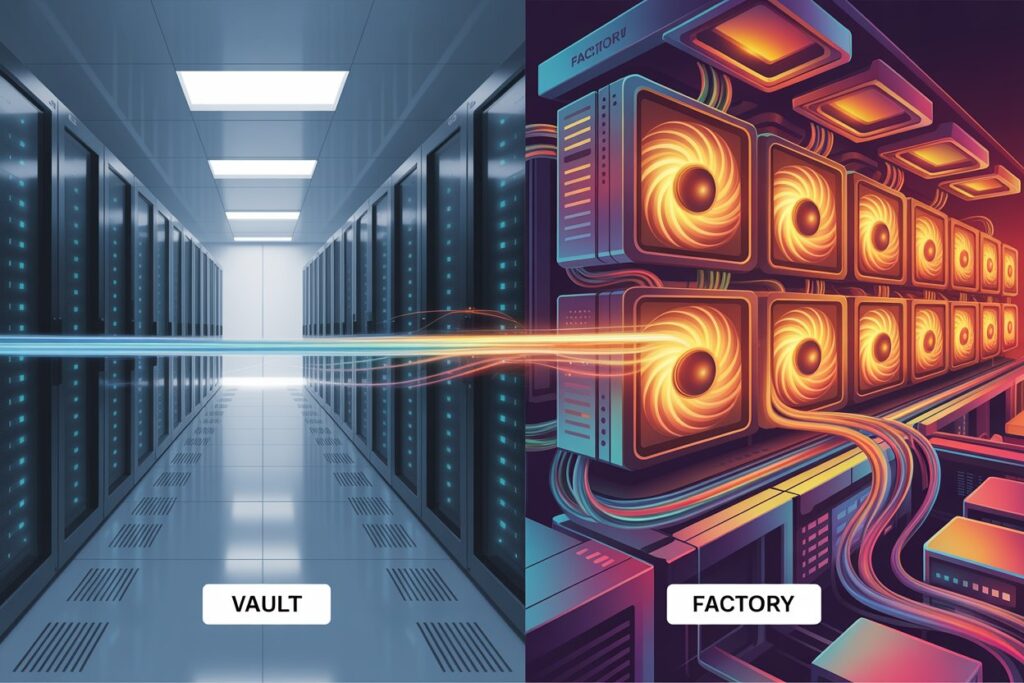

Most existing Australian data centres are essentially high-security digital storage lockers. They host cloud services, corporate data, financial systems and some government platforms. Think of them as the digital equivalent of bank vaults – essential for safekeeping information; but they don’t produce anything. They are secure storage of already-created data, not creators of new value. They are electronic filing cabinets only.

In contrast, AI compute infrastructure is more like a factory. It takes in raw material – raw data – and transforms it into something new: predictions, analysis, automation, code, synthetic media, drug discoveries, and content creation. Thus, the real value add isn’t in the storage, but in the compute. It’s the difference between holding onto metal ore and operating a steel mill.

And that’s where we’ve seen this sad movie before: Australia has spent decades digging up minerals and shipping them offshore to be turned into steel, batteries and semiconductors. Now for the sequel: Australia is now on track to do the same with data: we export our medical files, bank statements, personal records, business data and more – and get other countries do the thinking.

In doing so, we surrender not just value, but agency – letting foreign-trained algorithms decide who gets a mortgage, what medication your parents receive, and what your children see, read and believe.

Australia’s ability to turn it’s “electronic filing cabinets” into “thinking factories” is exclusively constrained by electricity generation and costs.

The energy difference is staggering. According to the International Energy Agency, a typical data centre handling standard cloud services consumes between 4 to 5 megawatts of power continuously. In contrast, next-generation AI compute centres – especially those housing thousands of GPUs – can require 80 to 100 megawatts per site. That’s 20 x more electricity needed.

Put another way: hosting office files and storing Gmail attachments is one thing; training and running AI models like GPT-4 or Google’s Gemini is like powering an aluminium smelter.

In short, the AI era marks a quantum leap in energy intensity. The infrastructure required isn’t just about space, cooling, and security – it’s about access to vast, stable, and cheap power.

Australia’s existing data centres are not built for this. They are optimised for uptime, security, and redundancy, but not for running thousands of GPUs or hosting large-scale foundation model training environments. And given our high energy costs, there’s little incentive to retrofit or upgrade them when cheaper, more low-cost, power-rich locations overseas are courting investment.

To put it plainly: having conventional data centres doesn’t make us competitive in AI. It’s like having a few tool sheds and claiming to be an industrial powerhouse.

What can be done?

The fix must be energy-first. If Australia is to compete in the AI era, it needs to make serious, coordinated reforms to energy and digital infrastructure. It starts with the political courage to reopen the nuclear debate.

Australian voters remain global outliers in their resistance to nuclear energy. Around the world, nuclear is becoming the go-to solution for powering energy-hungry AI clusters. France, the US and South Korea are integrating nuclear into national digital and industrial strategies. Even Saudi Arabia – despite its vast reserves of essentially free oil, gas and a growing solar capability – is choosing to power its multi-billion-dollar AI compute investment with nuclear. The attraction is obvious: stable, long-duration baseload energy that doesn’t depend on sunny skies or gas market volatility.

The revolution isn’t just in large reactors, but in small modular reactors (SMRs). Rolls-Royce in the UK is leading the charge with a new generation of factory-built SMRs that promise dramatically shorter construction times, lower costs, and flexible deployment. These reactors, projected to deliver 470 megawatts each, could be operational within five years and are tailor-made for powering high-performance AI precincts. US venture capital has taken notice. Investment into nuclear start-ups has surged to levels not seen since the Cold War. Yet in Australia, a decades-old federal ban means we’re not even in the game. If we want a seat at the AI table, we need a bipartisan pathway to nuclear very urgently.

While we’re rethinking generation, we must also fix the approvals bottleneck choking our transmission. Fast-tracking approvals near existing baseload generators or transmission corridors – especially if nuclear becomes an option – could dramatically cut lead times for powering new digital infrastructure.

Next, we need to think spatially. Just as Australia created industrial zones to support manufacturing, we now need to designate AI-ready energy zones. These should be pre-approved precincts for data centre development, co-located with reliable energy sources and backed by tax incentives, long-term energy contracts, and fast-track regulatory treatment. Think of it as a “Compute Coober Pedy” – not in geography, but in intent: a purpose-built AI hub with power, policy certainty and infrastructure baked in.

At the same time, the federal government should establish a sovereign AI and cloud reserve – a modern-day digital oil reserve. This would ensure that mission-critical applications like national security, health, emergency response and public service delivery can be hosted securely, onshore, and under Australian legal jurisdiction. If compute power is the new fuel, then we need a stockpile of it that we control.

Finally, we must make it worthwhile for investors to build here. Long-term power purchase agreements – 15 to 20 years in length – are already common overseas for large infrastructure projects. Offering these contracts to data infrastructure builders would reduce investment risk and help overcome Australia’s reputation for political and energy policy uncertainty.

The choice is still ours

If Australia fails to lower its energy costs and improve infrastructure certainty, the country will not be a player in the AI era – it will be a client state of those who are. That’s not alarmism. That’s simple maths.

What’s at stake isn’t just the location of server farms. It’s the locus of decision-making for everything from banking to biosecurity. A nation without compute is a nation without agency in the digital age. In a crisis, we may find ourselves relying on foreign servers, running foreign code, trained under opaque regimes – and by the time we realise the model is making the wrong decision, it may already be too late.

Australia has the technical know-how, the capital, and the demand. What Australia lacks is the political smarts and urgency. That must change. AI is not waiting for anyone.